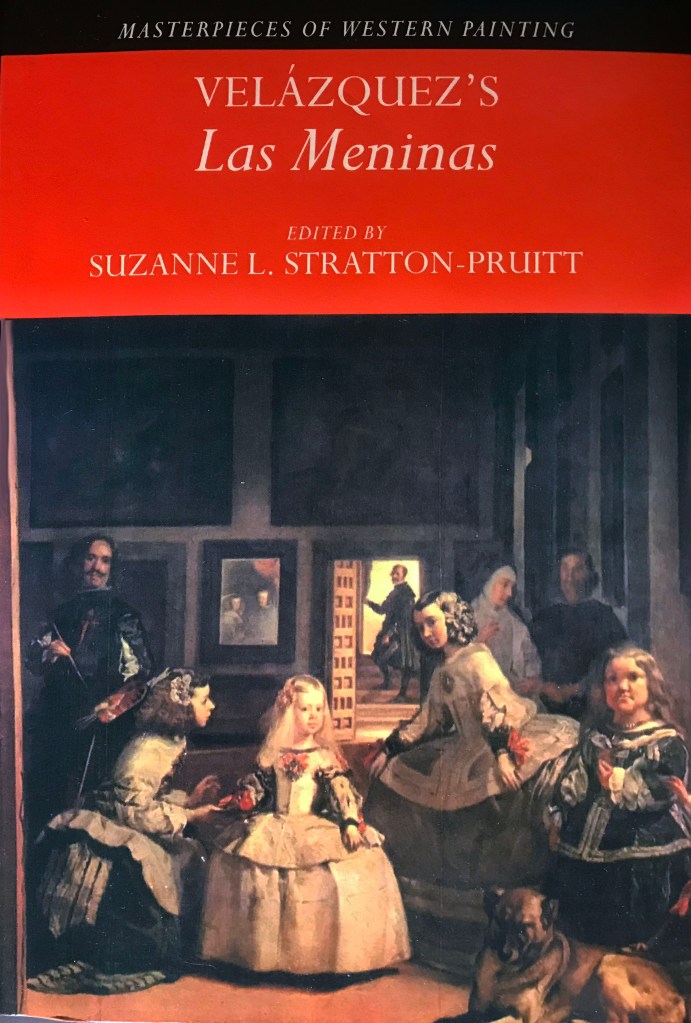

Periodically publishers issue a series monographs on individual works of art. This is still pretty rare in art publishing. There’s no tenure promotion given on single-artwork writing: what methodological theory can that advance? What new discovery can be wrapped around an entire book on a sole work of art? No, these, when they are written, are only done by scholars safe in their publishing careers.

This is really a shame. Art history started around the concept of the single work of art. Even graduate students in art history, who must, because of things like comprehensive exams, know about all the famous works of art, tend only to cover the highlight factors, the reasons the work is in art books. No graduate student can afford to sit down and read a little book on the aspects of a single painting. Whence the catholic scholar? I don’t know.

Of course, I was one of these graduate students. Through my career I made note of those book series devoted to single works. They are, to a title, still worth reading, still unique.

The Artists in Perspective Series (Prentice-Hall) early 1970s. Although not quite a series on a single work of art, the series, edited by HW Janson (of Janson’s History of Art fame) collected texts throughout art history on eminent artists. These often tended to center around a major work and therefore were nearly as handing as the series, soon to come, below.

Art in Context Series (Penguin/Viking), early 1970s. The undisputed acme of the genre. The brilliant publisher Alan Lane came up with the idea of short books on a sole artwork. To make it work, he appointed Hugh Honor and Jack Fleming, series editors, to commission the top scholars in the field to write these. Looking at the titles and the authors, it reads like a who’s who of 1970s art history. Each only around 100 pages, the scholar generally divided the book into small chapters addressing every approach art history (at the time) could address the work of art. Chapters would include social context, artist biography, commission (if any) and documents, preparatory drawings, reception theory and posthumous analysis. To this day anyone who wants to know how to write an art history paper could do little better than to scan one of these.

Trumbull : the Declaration of Independence

by Jaffe, Irma B. (New York : Viking Press, 1976.)

Poussin: The Holy Family on the steps

by Hibbard, Howard, 1928-1984. ([London] Allen Lane [1974, i.e. 1973])

Delacroix : The Death of Sardanapalus

by Spector, Jack J. (London : Allen Lane, 1974.)

Leonardo: The last supper

by Heydenreich, Ludwig Heinrich, 1903- ([New York, Viking Press, 1974])

Van Eyck: the Ghent altarpiece

by Dhanens, Elisabeth. (New York, Viking Press [1973])

Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even.

by Golding, John. (New York: Viking Press, 1973).